The following is a lecture given in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico on December 2017 to a group of U.S-based visitors from various backgrounds learning about the Zapatista movement. Alberto Vallejo Reyna is a scholar of indigenous spirituality and cultural resistance to colonization, Mesoamerican nawalismo, alternative cultural policies, and social movements. Translation by Linda Quiquivix.

This will be a brief talk where I share with you some very general ideas which, above all, will be provocations for us to think. What I present will not be finalized theses. Many of these ideas are from a research project I’m currently finalizing.

I’ll engage two themes. One is on the relationship between indigenous myths, legends, and resistance. It’s too bad that the women who asked the question yesterday about the relationship between indigenous myths, legends, and resistance are not feeling well and so are not here today, as that will be the first theme we cover.

The other theme has to do with an anthropologic-political reading of history. We will begin with this second theme.

Breaking from the Calendars of Power

There was a Jewish German philosopher who died in 1940 fleeing Nazi persecution. He’s a very famous philosopher, and one who Subcomandante Galeano and Subcomandante Marcos have referred to various times. In that sense, he’s one of many that the compas [Zapatistas] cite and refer to.

This philosopher, who was fleeing Nazi persecution in the 1940s, was named Walter Benjamin. As he fled, he carried a suitcase that held notes of his most recent work. This work was later published, and I really recommend that you read it. It’s a well-known text that you can easily find online. It’s a relatively short piece but it is so profound as a philosophical text. These are the famous Theses on the Philosophy of History.

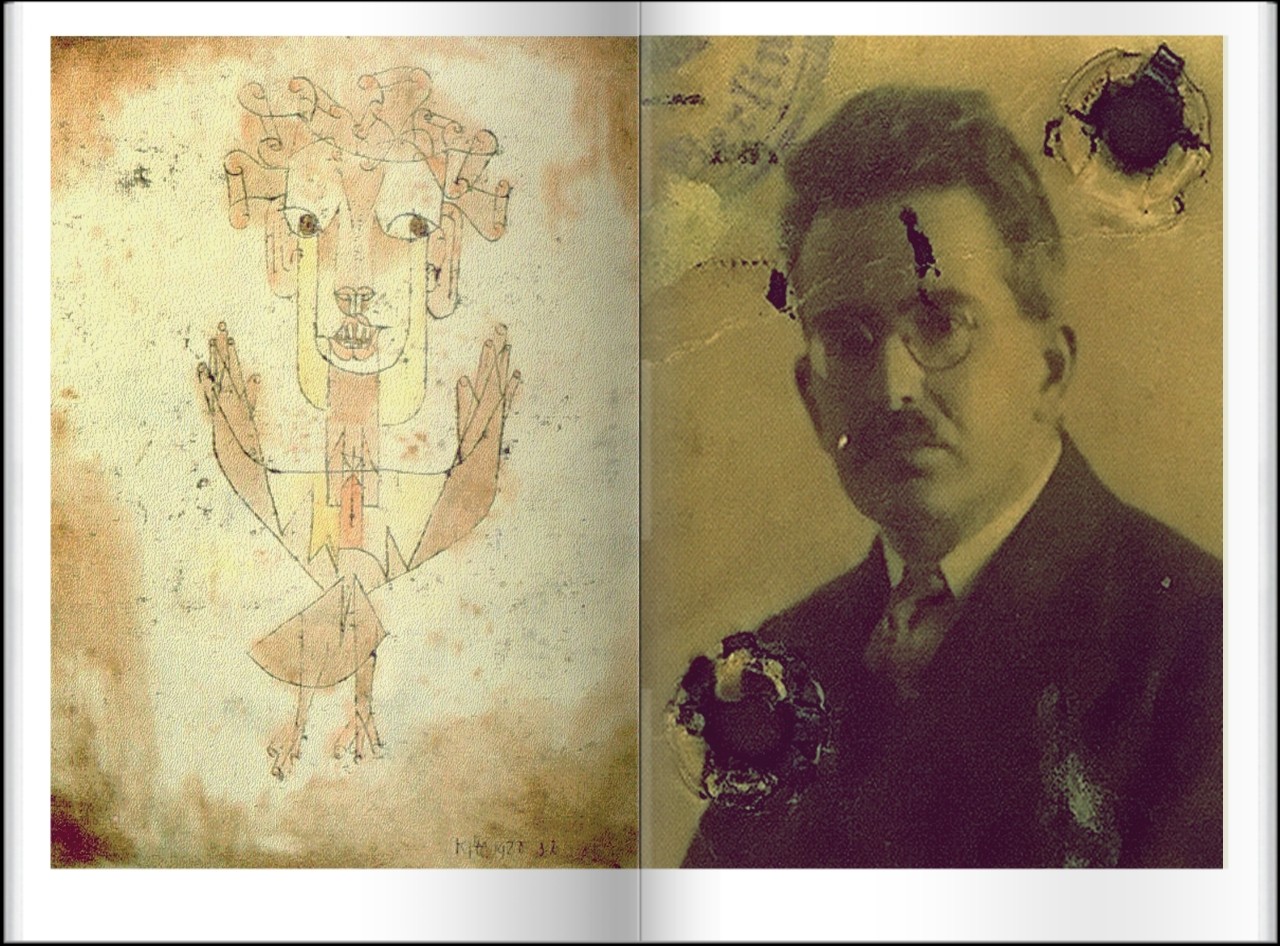

In this work, Benjamin refers to a painting created by his friend Paul Klee (Figure 1 and Figure 2), called “Angelus Novus,” which Benjamin describes as looking back, observing the past in horror. Benjamin calls it the angel of history because history, since the dawn of civilization to the present time, has been enormously difficult for the peoples of the world:

A Klee painting named ‘Angelus Novus’ shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistible propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress (Benjamin, “Thesis IX”).

What the Angel sees is a world where the powerful have imposed themselves on the people of the earth by way of thousands of massacres. That is, those currently in power are in power because of those massacres. If Walter Benjamin would have survived, he would have created a new theory of history that would have taken into account those killed. And as a Jew, in a way, he was reflecting from his cultural tradition a certain mysticism. Karl Marx was also Jewish, and Benjamin considers that the moment when theology and historical materialism come together, they would be invincible (Benjamin, “Thesis I”). So, this is a background to this reflection on peoples’ myths and legends, questions of spirituality, and resistance.

Under this logic, Benjamin considers that when Marx was imagining a society without social classes, Marx was secularizing an old Jewish idea—the idea of the Messiah, the idea where God comes to impart justice on a world full of sin, of injustice, of evil, and where through this justice, God resurrects the dead. Those dead are the massacred. So, the idea of the Messiah under Judaism is the idea of God coming down to earth to impart justice onto an unjust world.

This is how Benjamin proposes a messianic attitude in the reading of history and political activism. Messianic in the sense of universal justice, of imparting historical justice, of recognizing that the injustices of the present are a result of the injustices of the past. The past is not dead—the past is alive in our memory—and it’s the vindication of that memory, in the communication that we today establish with the vindications of yesterday, with the vindications of the fallen in the struggle for the freedoms and rights of humanity where Benjamin sees messianic mysticism as the object itself of historical consciousness.

Marx, with his materialist vision, sees this same idea but in a secular way where justice is imparted through the creation of a society without social classes. In this sense, Benjamin says that the massacred of the past have only one hope—those of us who are alive are that hope. They are waiting for this generation to vindicate them by remembering them and by imparting justice. The powerful always try to re-massacre them, to kill them all over again by forgetting them, and by imposing discourses that legitimize the power of the powerful through the power of the powerful of yesterday. This power reproduces itself by reproducing its calendars, its history, its vision of time, its vision of history.

In this sense, Benjamin was critical, for example, of the European social democrats [1] because they shared with the right the same vision of time, which is the vision of progress where history is always forward looking. This is a linear vision of time, which is a metaphor of a train advancing along the tracks. And here we can recall the old early twentieth-century Marxist metaphor that revolution is the locomotive of history. Benjamin believed that this was a political error because it placed revolution on the same lane as the right, as the capitalist notion—the notion of scientific progress, always advancing, always accumulating. And Marxists believed that society would be liberated via the force of technology and scientific development.

Benjamin critiqued them for placing all their hopes on scientific and technological development without considering the development of productive forces. He also noted that technologies of control would become more and more sophisticated. And today we see it, don’t we? Today’s modes of control are more sophisticated than they were a century ago—they’re technological. There’s an advance in the forms of control and repression [2].

And this is why Benjamin said that revolution is not the driving engine of history, but rather, revolution is instead its hand brake [3]. By putting a brake on progress, the inertia created by that brake would disperse us into different directions. To do so is to rupture from the continuum of the history of the dominant classes—it’s to break continuity with the narrative according to the established power. It means assuming new calendars that entail a rupture from the continuum, the continuity of power’s logic.

This is a metaphor for cultural diversity, of the different calendars and geographies as Subcomandante Marcos and the Zapatistas say. This is why they say that we have to create other calendars that are different from the calendars of power, that are different notions of time and space that do not reproduce the same notions of progress shared by the extreme right and the social democratic left.

This is because time and space are not separate. In fact, what the calendar of power does today is it imposes one calendar on the whole world that no longer has a territorial referent—that is, the Gregorian calendar is the same in China, the United States, and everywhere. What it does is organize the exploitation of labor at the global level, stripping away from us the relationship between time and its territorial referent. And this produces absurdities.

For example, right now in the southern part of the world, in this season of Christmastime, in Argentina it’s summer and it’s really hot, but they’re celebrating Santa Claus with snow. This is because what the calendar guarantees is the consumption of capitalist commodities, and there is no longer a relation to territory. It’s an absurdity, and that’s one example.

It’s why, when the Zapatistas ask that we take back our calendars and geographies, they are connecting with the old revolutionary tradition that saw that the time of power was the principal instrument of domination. They are reconnecting with the old idea that the time of power needed to be destroyed and broken away from, and that a new time and space needed to be created.

For example, the French revolutionaries in 1789 created a new calendar which was not the Gregorian Christian calendar [4]. They understood the Gregorian Christian calendar as the calendar of power, for it is a calendar that hearkens to the Roman Empire—a calendar of power without referent to territory. So, the French revolutionaries created their own calendar that aligned with the seasons of the year. And it’s an other calendar. In this sense, we can understand the beautiful paragraph Benjamin wrote in “Thesis XV”:

The awareness that they are about to make the continuum of history explode is characteristic of the revolutionary classes at the moment of their action. The great revolution introduced a new calendar. The initial day of a calendar serves as a historical time-lapse camera. And, basically, it is the same day that keeps recurring in the guise of holidays, which are days of remembrance. Thus the calendars do not measure time as clocks do; they are monuments of a historical consciousness of which not the slightest trace has been apparent in Europe in the past hundred years. In the July revolution (1830) an incident occurred which showed this consciousness still alive. On the first evening of fighting it turned out that the clocks in towers were being fired on simultaneously and independently from several places in Paris. An eye-witness, who may have owed his insight to the rhyme, wrote as follows:

Who would’ve thought! As though

Angered by time’s way

The new Joshuas

Beneath each tower, they say

Fired at the dials

To stop the day

Thus, to make revolution is to stop power’s time, break its continuity, and inaugurate new calendars.

Mesoamerican Calendars and Geographies

That’s one example, but all over the world, people have different calendars. For example, here in Mesoamerica, there exist different types of calendars. Very famous with anthropologists and archaeologists are the region’s ancient hieroglyphic writings. And Maya mathematics are very well known all over the world. These are mathematics that, above all, seek to calculate time from the starting point of the cosmic cycles of the sun, moon, and planets.

I calculate that there are five types of referents. For example, if you go to any Mesoamerican Maya city, be it Teotihuacán, Palenque, Chichén Itzá, these were cities that were designed as observatories. The city’s layout has astronomical referents.

The most ancient city in Mexico is the city of Cuicuilco, which is located south of modern-day Mexico City. There is a giant caracol [conch] there, which is a round pyramid. The National Indigenous Congress met there in 1997 when the Zapatistas arrived in Mexico City with 1,111 delegates. From that place, which is Mexico’s most ancient city, they made a pact: the confirmation of the National Indigenous Congress.

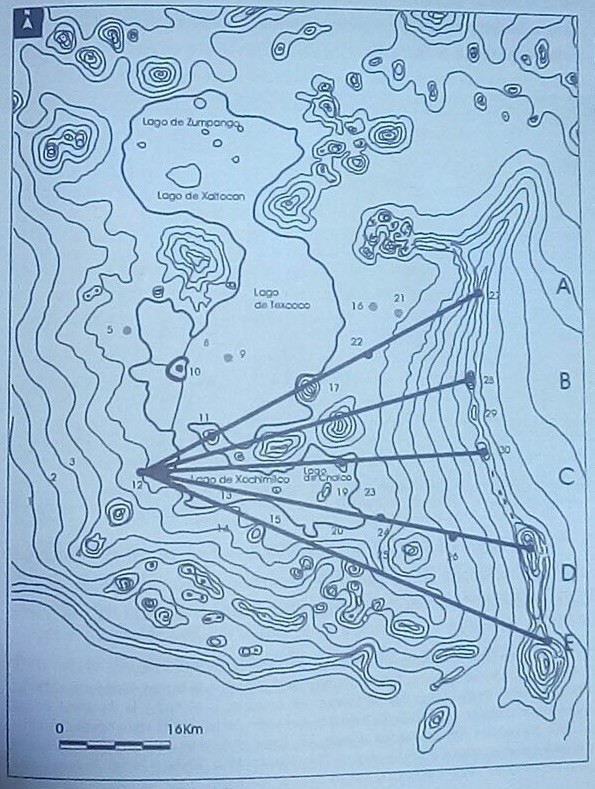

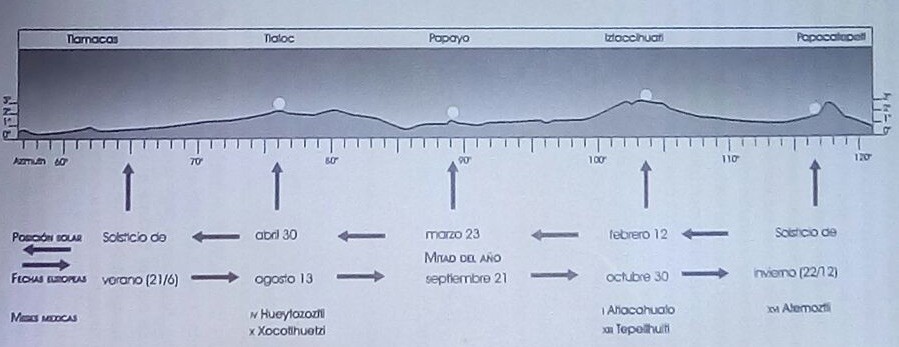

Perhaps the idea of the caracol is a very ancient idea. In the caracol of Cuicuilco, there is a big pyramid, and behind it there’s a big hill which is today called the Forest of Tlalpan. There is a big observatory there. On the other side, there is another hill, which is today called the Hill of Zacatepec. And from those two observatories, in relation to the giant, round pyramid, viewing the landscape you can see Popocatépetl, the Smoking Volcano, which is one of the tallest of Mexico. Then there is Iztaccíhuatl, which is the Sleeping White Woman. And then there is the mountain range where in the far beyond you see Tlaloc, the hill of the God of Rain (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

From these two observatories, you see the changing path of the sunrise throughout the year, each day the path shifting a little bit this way, and then coming back. They used to cut slivers in the forest so that they could see the precise location of the solstice. And in this manner, they created their astronomical calendars. This calendar doesn’t change—let’s say, it’s very precise as it takes millions of years for nature to change, and from the lifespan from a human dimension, it’s precise. It serves as a referent to study the world. Out of the five referents, this is level one: astronomy, and it is very precise.

From there, compare level two, which is meteorological. This has to do with the clouds, the winds, the rain, and lightning. With this, they can more or less calculate when the time for rain will be.

The third level is ecology. There they can compare the behaviors of plants and animals in relation to meteorological time. They can calculate the cycles of plants and animals with a relative level of precision.

The fourth level is the sociological level—you organize society for work and for celebrations to make the best of the ecological and meteorological cycles for agriculture, food production, and hunting.

The fifth level is the psychological level—this allows you to view people’s behaviors in relation to ecological time, sociological time, meteorological time, and astronomical time.

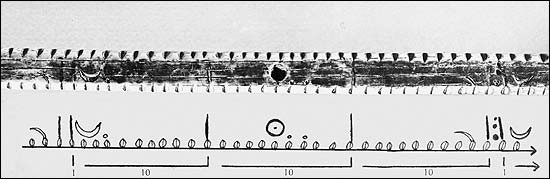

This is a general basis of the Mesoamerican notion of time. It actually comes from the hunters and gatherers of Siberia from 35,000 years ago. Archeologists have found the most ancient calendars in Siberia in bones and stones that make the shape of caracoles that align with the cycles of the moon, as the cycle of the moon is more sophisticated than the cycle of the sun, as it is a larger cycle. This was inherited from Siberia to when they would populate the Americas.

In ethnographic studies of indigenous peoples in the United States and Canada, archeologists have found what they call the “Guardians of the Calendars” (Figure 5) that still utilized bones that look very similar to those that were created in Siberia 35,000 years ago. Ethnographers found that even in the early twentieth century, there were still indigenous people using this calendar.

So, this idea of utilizing the astronomical referent to understand territory is one of humanity’s most ancient sciences. It’s always adapting to the territory that you are exploring. Humans, for the majority of time, have been explorers—we have been migrants. This is how the entire American continent was populated. Exploration took place and nature got to be known. This is how corn, sunflowers, cacao, everything could be domesticated. This is how civilization could be created. And that’s the patrimony of this continent, which gave us many foods that we continue to consume, such as tomatoes, squash, and corn.

Capitalism and Fascism as Illness

In Mesoamerica, there also exist predictive calendars. They form a system that allows human psychology and human diversity to be understood. For example, today in Guatemala, that calendar is still known. It’s called the “Counting of the Nawales.”

The other day, I mentioned that “nawal” is translated as “costume” because it is the movement of time that’s always changing nature, as if it were changing costumes. This is why there are different celebrations: for the times of rain when the frogs sing, for the times of drought where there are other types of animals and there are different costumes.

These are metaphors to understand human diversity. They say that every human has a nawal—that is to say, a costume, a personality, a role in society. We have a profession, a style. And that’s studied with the counting of the nawales.

In Guatemala, where this counting of the nawales continues to be preserved, they say that the most common illness of our time is that people don’t follow their nawal. That is, that people don’t develop their spirit. That rather, we chase instead what capitalism imposes on us.

For example, you have to become an accountant so that you can get a job, so that you make money, so that you can consume. You’re doing work that is different from what your spirit is. And this is why people have neuroses, psychoses, depression—in other words, mental illnesses that provoke you to not follow your destiny. Said another way: you do not relate with your profound self. The Maya healers of Guatemala see that this is the most common illness of our times. They say that capitalism is an illness.

Here, let’s take a pause so we can connect this Maya notion with the theory developed by a German psychologist who was a contemporary of our philosopher Walter Benjamin. This psychologist’s name was Wilhelm Reich. He died in the United States in prison because everyone was after him. In Germany, the Nazis were after him for being communist. He was a member of the German Communist Party, and the Communists expelled him for being depraved. It’s what the Communists thought because he, as a psychologist, created within the Communist Party in the 1920s what is called the Sex-Pol (sexual politics).

He used to say that neuroses had to do with peoples’ lack of orgasms, and in order to make revolution, the workers needed to be healed with a sexual politics. This is why it was called the Sex-Pol. He was a precursor of a systematic sexual education. He considered that fascism, more than an ideology, is a psychological condition.

There’s a very famous essay that Wilhelm Reich wrote “The Mass Psychology of Fascism.” It’s fascinating, and let me see if I can more or less explain it. It’s the 1920s, and the film industry is growing, as is radio and mass communications media. Our philosopher Walter Benjamin wrote a book called The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, which discussed how a work of art can be reproduced in mass quantities. Benjamin is predicting our era of media and the power that these media have to manipulate mass psychology.

It’s a complex subject that requires study, but we could summarize that Wilhelm Reich argues for a science of sexual or libidinal economy built on the sociological foundations of Marx and the psychological foundations of Freud. Its objective is to understand those complex psycho-social mechanisms that drive the oppressed classes, who are trapped in psychic contradictions between their real economic oppression and desires to behave, and their desires to misbehave and revolutionize society. From that psychic contradiction, Reich observes that once that masses assume the authority of the father and the state, they reproduce the social system because they want to see themselves reflected in the state.

If psychoanalysis reveals to us the effects and mechanisms of sexual repression and its pathological consequences, Reich discovers that sexual inhibition structurally modifies economically oppressed human beings in such a way that they act as massified individuals, feeling and thinking against their material interests, supporting their oppressors. This is tantamount to saying that they assimilate the bourgeois way of life and its world of illusions as something moral, and they base the construction of their psychic life on desires that are in harmony with the mechanisms of cultural consumption of the economy of commodities, of which the capitalist economic system is objectively based.

This means that society constructs desires that lead most people to want for themselves something that they are not, but something that is functional to the capitalist economic system and the patriarchal society that sustains it, which Reich considers an effect of the mechanisms of sexual repression with its derivative pathological consequences.

The desire of the oppressed classes to resemble the bourgeoisie generates a psychic contradiction between their desires and their economic reality, a contradiction that manifests pathologically as anguish, generalized neurosis, and in extreme cases, as psychosis. That’s why Wilhelm Reich, like the Maya, see that the principal mental illness is that the masses do not self-actualize in spiritual harmony between their social and cultural condition, the territory they inhabit, and relationships with their contemporaries.

This is a discovery of the psychic power of mass culture, which alienates people’s being—their nawal—and favors bourgeois identities in the oppressed classes. Thus, in accepting the authority of the father and of patriarchal society, they accept their own submission to the political power of bourgeois society. These are fascinating, controversial, complex topics. They are not easy to study and understand, but they are fundamental to understanding the ways in which power is reproduced.

The first who used the mass psychology systematically were the Nazis. They created a propaganda ministry, and a language of film, radio, and television. And we know what the Nazis did in manipulating people’s psychology. And that’s what capitalists do today for commodity consumption. It’s a magic, a power to manipulate mass psychology. In the terms of Wilhelm Reich, it would be a massive psychological illness. This why Wilhelm Reich thought that, more than an ideology, fascism was an illness.

Thus, fascisms—for example, Trump, Hitler, or whatever fascism—do not appeal to reason. They instead appeal to prejudices. They appeal to the irrational. They appeal to what biologists refer to the “lizard brain”, which is territorialist and is always distrustful of the other. That’s what fascism does: it appeals to those base energies and instincts, and manipulates them politically. That’s what politics is about. As Michel Foucault says, politics is above all, getting others do what you want them to do. Politics isn’t really the struggle between ideologies, but more about provoking certain behaviors. And this is the manipulation.

This manipulation has rendered ill the majority of humanity, and it’s what politicians do within electoral systems. They don’t appeal to reason, they appeal to instincts in order to manipulate people who have certain behaviors.

Our Nawal as Our Life’s Work

That is the time of fascism and power. And that’s why it’s so important to recover those other calendars and reconnect with territory, connecting us with our self, our nawal. It implies an effort because the nawal is not something that is predetermined, rather, it’s work that we have to do.

When the Maya in Chiapas translate the word nawal into Spanish, they translate it as “the art.” In other words, each one of us has an art that we have to develop. It’s not something that’s predetermined but, rather, it’s our life’s work. It’s to develop our costume or personality as an actor in the world. Because in the end, the world is a game. You can either play the game of fascism, which is imposed on you like in the Pink Floyd film “The Wall”: something very standard, mechanical, consumerist. Or, you can develop your art.

That’s why our philosopher Walter Benjamin used to imagine that a communist society—a society without classes, a just society—would create a citizenry of artists. And he saw that we would observe ancient gods as artists.

For example, in Maya myths, the god-creators of the world are artists. They created all of the arts of the world, for example, math, agriculture, medicine, pottery, textiles, architecture—all of the arts of civilization. So, ancestral gods, like a mythological projection, are nawales, they are artists.

So, every human, we need to develop our art and evoke the ancient gods. It’s really interesting. It implies a change of civilization because capitalist civilization wants to maintain a society that is ill and manipulatable. And that’s what we’re living.

This isn’t just created by states. It’s also created by different interest groups through communication media, educational systems. They create a certain notion of time and space, which is a capitalist notion of progress where we’re all on the same train going in the same direction, always forward moving.

So, an anecdote: When Obama won the presidency in the United State, and he traveled to South America for a meeting of presidents of the Americas, Hugo Chavez came up to Obama and he gifted him a book by Eduardo Galeano called The Open Veins of Latin America. This is a book where Eduardo Galeano recounts the history of colonization of the Americas. Days later, journalists asked Obama what he thought of the book that Hugo Chavez gave him. Obama responded something like, “Well, these people are thinking about the past, and we need to think about the future.” That’s the attitude of the powerful: always to forget the past and think only about the future. But, as Walter Benjamin explained to us, the Angel of History looking back in the past sees the history of massacres.

This illness that we have is the trauma we’re living of all that history. We are traumatized because they massacred our ancestors. All of us who are not the Rothschilds, the Soros, the British royals, the Rockefellers—we are all children of the massacred if we are not a part of these families. There was a moment when our ancestors were massacred, and we ended up in the cities where we were born, looking for work, adapting, and what we have now is what we humbly have been able to acquire in life.

That’s why when the Zapatistas say “other calendars, other geographies,” they connect with Walter Benjamin so we can communicate with the massacred in history. They’re waiting for us to be the generation that imparts justice and resurrects them. And they will be resurrected when there is justice.

Here, in San Cristobal, there is a church here where they worship a christ who they call the “Just Judge.” He is an indigenous christ. His nawal is a christ nawal. He is a christ of justice. It’s one of the deities of many that exist in these territories, in the ways in which I’ve been explaining about how ancient gods, ancient nawales, have Christian costumes. And psychologically, people are not aware of it, but is reconnecting to a longing that we all have.

From Chiapas to Central America, the Just Judge is one of the principal deities. That’s an example of how spirituality is related to resistance.

[Alberto’s daughter, Flor:] Can I say something? I just want to comment something about the people of Guatemala who say that we don’t follow our nawales—that we just don’t follow our destiny, to say it one way—and I think our destiny is that we’re losing this sense of life, because for me, the sense of life is death. Imagine us living forever. Imagine us, if we can’t die, we wouldn’t put any effort into living. And that’s what we’re doing right now. We don’t live close to death, and that’s what makes life boring. And to hide these kinds of things, the government gives us movies like “The Avengers” and “Spiderman” and things to make us feel better—stupid things. And that’s an idea that’s really Japanese because their people used to be really close to death, like Samurais. They were really, I don’t know how to explain it, but they were really big on this idea. And the United States has been changing it to have an occidental way. Illnesses are because we lose a sense of life. That’s what I think. [Alberto:] Well, she’s said it. And I do think that this has to do with it a bit.We can continue on and talk about other themes, I don’t know. For example, I can evoke Andrés Aubry with all my respects because he was very wise and knowledgeable of the history of Chiapas.

Aubry used to be critical of anthropologists because, he said, they didn’t study the causes of the exploitation and domination of the people. Instead, what they focused on was studying rituals and carnivals. So, he came up with a metaphor: “It’s as if we want to study and try to understand the culture of the United States by studying Halloween.”

Aubry used to say it in a critical way, but I think that Aubry was wrong. We actually do need to study US culture through Halloween because there what we see is the fear that the Other—the fear that the Other will destroy you. So, what you do instead is destroy it.

So, all of the hero mythology, as Flor was mentioning…

[Flor:] They don’t destroy you, they give you candy. [laughter] [Alberto:] And you destroy it, no?There, what we can understand is that power is cultural and that it’s an illness. It’s a fear of the Other. The Other is seen as a lizard brain that is a threat. And that’s an illness that anyone call fall into, anyone from any place in the world. But also, any person in the world can learn from the Other, seeing the Other as a mystery—a mystery of the unknown. It’s an attitude that can help you grow in life.

In 1948, after WWII, after the Holocaust and all of that, the United Nations’ UNESCO commissioned a French anthropologist whose name was Claude Lévi-Strauss to investigate to see if there was such a thing as racial superiority. Lévi-Strauss showed that there was not.

On the contrary, he showed that all of the planet’s civilizations emerged from diversity, as much in Mesopotamia as in Egypt, India, China, here in Mesoamerica, in the Andes. In all places of the world where civilizations were grown, they emerged from contexts of cultural diversity—of different languages, of different arts, of different peoples exchanging all of these things is how civilization emerges. This goes against the idea that the Greeks are only the badasses [chingones] of history. The Greeks themselves emerged from diversity.

So then, that attitude of learning from the Other, of seeing the Other as a mystery, is a human attitude that needs to be encouraged. And there are so many different examples of this. Here in Mesoamerica, the gods of the mountains, for example, are white, they’re blond, they’re gringos. The gringo is a mystery. The Spaniard is a mystery. Christ is a mystery. And so, the Other is someone you can learn from. And that’s an attitude that needs to be encouraged. And as I’ve said, it’s a process, it’s an effort.

That’s why the politics that the Zapatistas engage in is one undergoing that effort. They’re learning from the world. And that’s why they convoke the “intergalactic”—they convoke everyone in resistance in this world and other worlds. And they convoke the scientists. And they convoke the artists. They’re undergoing that effort to learn from the Other.

It’s an effort of learning, of making your life, where you’re not whole—that is, where the “I” is not complete without the Other. Where the Other completes me because the Other is a mystery. It’s with the Other that I learn through dialogue, critique, debate, and even in many languages, in many spiritualities, in many territories, in many times. Because the Other is us, and they’re also the ancestors of us all.

Participant discussion

[Participant:] In Greece, a congealing of power against the feminine took place, which is how the Greeks became the supposed badasses of history. [Alberto:] Yes, history changes when we think this way. And that’s why I began with Walter Benjamin, who was thinking about developing a different vision of history and asking that we research it all over again because what they’ve taught us is history from the point of view of power. So, we need to reconstruct history, and that’s an effort of our generation in order to connect with our ancestors. In fact, indigenous peoples say that the future is to your back because you don’t know what’s going to happen, you don’t see it. But what you do see is the past. [P:] The Greeks and Romans disappeared for a while in the “Dark Ages” of Europe, and they were resurrected by the colonial effort to create a glorified history, and to bring the civilization of the colonizer as superior mythology. [A:] I’d like to go on the record and state that what I think is that not all Greeks were the same. The ones that were vindicated were certain ones, that it’s possible that this happens in all cultures. For example, here in Mesoamerica: the Aztecs. I think that from there we can understand many of Mexico’s traumas.Mexico’s origin myth says that the Aztecs came from Arizona or somewhere in the north, migrating from Aztlan, the “land of herons.” There, their gods told them to migrate south. They were led by twin siblings—a woman and a man. The woman’s name was Coyolxauhqui (in Náhuatl, “adorned with bells;” coyolli: bells, xauhqui: adorned), and the man’s name was Huitzilopochtli. The woman was very wise and very kind, and everyone loved her. And her brother, Huitzilopochtli, was a hunter, and he represented that masculine energy of being up in the mountains with his bow and arrow.

In contrast, Coyolxauhqui used to create wonders in the kitchen. As they were migrating and they needed to figure out what to eat because they didn’t know what was edible, she was always discovering those foods they could eat. And so, the people loved her very much because she saved their lives. She made cooking an art form, and she would also find medicines, and she was very sweet.

By contrast, Huitzilopochtli was very conceited and arrogant. And he was jealous of his sister. And so, he conspired against her, provoking everyone to rise early one day and abandon her in the desert so that she could die. But because she was very smart, and in addition the people loved her very much, they were able to rescue her.

Still, Huitzilopochtli tried this over and over again until he finally killed her—except, she would always come back to life. So, Coyolxauhqui is represented as a dismembered woman—cut up arms, cut up legs, cut up head (Figure 8). It’s an image of a cut-up woman because Huitzilopochtli would always go cutting off one of his sister’s arms or legs so as to limit her power. But she would always come back to life. Until finally, he cut out her heart. And they say that he then sent her heart to be buried in the middle of the lake in Mexico City.

Recall that Mexico City is a lake with an island in the middle. That’s where they buried her heart. But so that she would not come back to life, Huitzilopochtli placed a stone over her heart in order to smother it. But from that stone, a cactus grew, giving the prickly pear—red for the blood of Coyolxauhqui. In that cactus that grew from that stone in the middle of the lake, the eagle came to eat the serpent—that’s the symbol of Mexico, and that’s a hieroglyphic you can read, “meztli xictli co” which means “in the navel of the moon,” which is Coyolxauhqui.

So then, the Mexicas, or the Aztecs, are warriors who worship Huitzilopochtli, who is the hunter-brother, which is why they could conquer villages and organize the Flower Wars where they would kidnap the young, warrior males, cutting out their hearts, sacrificing them to Huitzilopochtli, taking the strength of the people, and making it possible to conquer them. So, there we see an example of how these energies can exist in any people.

The Aztecs, we might say, are like the Greeks of Mesoamerica: male chauvinists, jealous of their mother who they dismember, conquering the male youth of the Other in order to keep the women. I don’t know, but I think that maybe that’s where we might study the psychology of Mexican fascism. As they say, fascism is an illness, and it can express itself differently in any peoples of the world, through different symbols.

[P:] This explains everything, I finally understand! [laughter] [A:] So, it’s not just the Greeks. In other words, in all peoples there are both nawales and mentally ill fascists. [P:] Yes, it’s very important to not romanticize the pre-Hispanic. [A:] In pre-Hispanic Mexico, there existed tendencies just like in Greece. In Greece, not all were the same. History needs to be researched all over again, and the traumas that we carry need to be understood in order to heal. Every country, every people has its traumas. We could go on, but now it’s time for lunch.##

Footnotes:

[1] Benjamin’s critique of social democracy includes both the strictly social Western tradition and the Eastern European, or Stalinist version. For Benjamin, the doctrine of Stalinist “communism” is no more than a socialist form of social democracy, which emerged in Germany towards the end of the nineteenth century and would become the revolutionary political culture throughout the twentieth century.