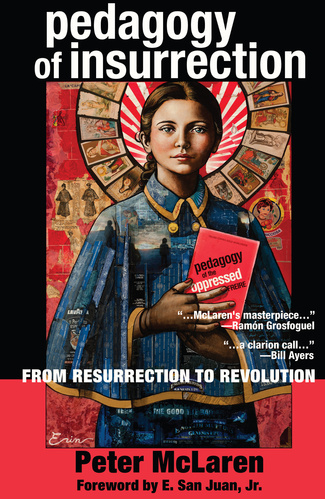

Renowed critical pedagogist Peter McLaren’s newest text, Pedagogy of Insurrection: From Resurrection to Revolution (New York: Peter Lang, 2015), combines humanist and orthodox Marxism with Christian communism, democratic socialism, concrete utopianism, and anarchism to intransigently denounce the capitalist system’s relentless oppression of humanity and prosecution of zoöcide, or the wholesale destruction of life.

Renowed critical pedagogist Peter McLaren’s newest text, Pedagogy of Insurrection: From Resurrection to Revolution (New York: Peter Lang, 2015), combines humanist and orthodox Marxism with Christian communism, democratic socialism, concrete utopianism, and anarchism to intransigently denounce the capitalist system’s relentless oppression of humanity and prosecution of zoöcide, or the wholesale destruction of life.

Underlying Pedagogy of Insurrection is the “Critical Rage Pedagogy” that McLaren marshals against the prevailing dominance of brutality and unreason, a four-movement cathartic symphonic play that is to be enacted by twelve actors who characteristically declare, “You [bourgeoisie and State] sicken us with your scandalous degradation of human life!” (McLaren, 400). This type of pedagogy echoes La Digna Rabia (“Dignified Rage”) of the Zapatistas and John Holloway’s concept of “The Scream”:

“All human and non-human animals inhabiting the planet have been stuffed stone-eyed into the vaults of capitalist social relations, a mausoleum of tortured beings writhing in the toxic vomit of the earth. We weep with all sentient beings […] (4).

“Ethical deficiency and logical contradiction are connected insofar as capitalism has dehumanized humanity and treated [it] as inert matter that can be swept under the toxic ruins of the world’s industrial wasteland” (26).

“Capitalism […] has strapped us to the slaughter bench of history, from which we must pry ourselves free” (67).

McLaren places Jesus the Nazarene centrally in his analysis of the depravity and crisis of capital. In the first place, the image of the suffering Christ stands in for exploited and excluded humanity and degraded nature, while secondly, the author stresses that socialist movements should consider Christ’s prophetic teachings on love and justice as “both apocalyptic warning and cause for joy in the possibility of redeeming the earth from ecocide and bringing about an alternative” to bourgeois society, thus realizing the regeneration of “risen beings in history” (13, 48).

The author refers to this “radical exterior” as the Kingdom of God, which is messianically proclaimed as being at hand, though not yet fully revealed. Christ, raised in the context of Bedouin communism, was the insurgent critic of Roman imperialism and class society, radically proclaiming the equality of all humans. These were acts for which he was politically imprisoned and crucified for sedition, and he both symbolizes and inspires McLaren’s perspective (103-26). As the prophet declares at the synagogue in Nazareth at the outset of his ministry,

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach the gospel [good news] to the poor; he hath anointed me to heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, […] to set at liberty the oppressed, to preach the acceptable year of the Lord” (Luke 4: 18-19).

Like Jesus two millennia ago, the revolutionaries of today have “a new era to proclaim” (McLaren, 124). McLaren defines the present project of critical pedagogy as calling into question the sense that “There Is No Alternative” (TINA) to “inequality, injustice and suffering among humans and non-human animals” while working to build an “anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist, anti-racist, anti-sexist, anti-heterosexist, and pro-democratic” movement instituting “counter-hegemonic globalization” (35-9, 154).

Invoking Bertolt Brecht, Augusto Boal, and his mentor Paulo Freire, McLaren explains the centrality of conscientization to critical pedagogy, which “invites students to understand everyday life from the perspective of those who are the most powerless in our society,” toward the end of transforming these very inequalities (141). Amidst the structural genocide that is global capital and the “future anterior” of ecological conflagration for which it is responsible, McLaren identifies the need to escape from the rule of the bourgeois “world-eater” as a categorical imperative (67).

Some of the images and means of resistance McLaren advocates include struggle by Giorgio Agamben’s “non-state” (humanity), the Gramscian “war of position,” Raya Duyanevskaya’s permanent revolution and “absolute negativity,” the ecological general strike called for by the Industrial Workers of the World’s Environmental Union Caucus (IWW-EUC), and the general unification of workers, peasants, intellectuals, and activists (92, 102).

Yet, while the author expresses his solidarity with anti-authoritarian youth of today, the “heirs to Spartacus, the Paris Commune, the Levellers, the Diggers, the Ranters, the Zapatistas, and the sans-culottes,” he also expresses his belief that Chavista “twenty-first century socialism” represents the best example of contemporary revolutionary struggle, in light of Hugo Chavez’ efforts to promote councils, cooperatives, and worker self-management in Venezuela, and the State’s successes in reducing poverty in that country (133, 175-8).

McLaren focuses his attention on developing a “revolutionary critical ecopedagogy” in the essay “Seeds of Resistance.” Here, he writes that ecopedagogy is rooted in working-class ecological struggle and the “environmentalism of the poor,” as expressed in such “spaces of hope” as the Chipko forest movement and Cherán, Michoacán (301, 316-7). The author emphasizes the relevance of the Marxian critique of political economy to an understanding of the accelerating ecological crisis, and, with an eye to the urgent question of the timeframe for possibly averting utter environmental self-destruction, calls on ecopedagogical activists to link efforts with existing decolonial efforts “of all kinds” to redirect the course to “living hell” toward which capital is propelling us (306, 315-6).

In a similarly moving fashion, McLaren and co-authors Lilia D. Monzó and Arturo Rodriguez denounce the transnational arms-trade racket in U.S. and Mexico, which upholds the military, police, and privilege, leaving in its wake the destruction of countless tens and even hundreds of thousands of lives, who are reduced to “expendable communities” or “unpeople,” the latter being historian Mark Curtis’ term. While U.S. inner-cities are devastated by gun violence and a quarter-million small arms are trafficked to Mexican cartels annually, thus perpetuating ongoing conditions of civil war, “the feral, vampire-like gun capitalists laugh all the way to the bank” (359-67).

The solution to such depravity and tragedy, conclude McLaren, Monzó, and Rodriguez, is to construct an anti-capitalist alternative—“Peace through socialism!”—and though they “denounce guns and all destruction of humanity,” they do not preach strict non-violence going forward (370, 415).

Insurrection—for Libertarian or Authoritarian Socialism?

In Pedagogy of Insurrection, McLaren makes a cogent, clarion call for upending the capitalist system through ubiquitous forms of multitudinous resistance—a globalized Marcusean “Great Refusal”—and for this certainly merits a great deal of praise. Yet certain questions bear raising in reflecting on the author’s presentation.

As Peter Hudis notes in his review of the text, for example, McLaren does not discuss or even really acknowledge the contradiction of “Bolivarian petro-socialism” in Venezuela. It remains highly questionable to claim that “Chávez followed the principle of buen vivir”—that is, an indigenous Andean concept, Sumak Kawsay, that espouses human well-being in harmony with nature, not the Marxist development of the productive forces—during his tenure (178). In “Comrade Chávez,” McLaren admittedly concedes Bolivarianism to essentially be social democracy, but he insists it could somehow become a revolutionary prelude to post-capitalism (174-5).

Similarly ideological treatment of the “socialist” governments of Evo Morales and Rafael Correa in Bolivia and Ecuador, respectively, is to be found within the text as well (92-4). No comment is made about the manifest contradiction between these two leaders enshrining constitutional protections for Pachamama while greatly accelerating extractivism.

In parallel, McLaren presents Che Guevara as an egalitarian, anti-bureaucratic militant, thus hiding the Argentine’s Stalinism from view—indeed, he defends Che against the charge of having “fallen prey to the most regressive manifestations of romanticism,” i.e. “Blanquist or Bakuninist form[s] of adventurism” (218). While it is questionable indeed to associate Bakunin with historical regression, it bears stressing that tensions clearly exist between McLaren’s declared affinity for Che Guevara, the advocate of hatred and State terror, and Jesus Christ, who favored non-violent forms of non-cooperation, according to the Gospels.

Pedagogy of Insurrection, in a sense, speaks to the ambiguity of McLaren’s insurgent political philosophy. The author describes himself as a revolutionary Marxist, a Roman Catholic socialist, and a critic of the state capitalism of the USSR (111-2). But as we have seen, he defends the social-democratic Latin American governments associated with the “Pink Tide.”

In the book’s coda, “Critical Rage Pedagogy,” he expresses his desire for a “counter-hegemonic state,” while earlier he affirms the value of the dictatorship of the proletariat (396, 315). Part of his attraction to Che is due to the “hope [Guevara gave] that smashing the old state and creating a new one is still a possibility” (216).

In terms of environmental sociology, moreover, the sources McLaren calls on—Álvaro García Linera, John Bellamy Foster, and Samir Amin—are associated with the authoritarian socialism of Monthly Review, while Murray Bookchin and social ecology are mentioned but once in the text, in passing (71, 94). Yet, as mentioned above, McLaren also hails the revolutionary anarchist call made by the IWW-EUC for an ecological general strike, and he locates the essence of the Russian Revolution in popular self-management through the soviets, not Bolshevik hegemony over the State apparatus (125).

The most faithful expression of his views, perhaps, comes in the synthesis he proposes while raging: “We stand firm for a multi-tendency revolutionary democracy that advocates direct forms of mass-rule” (425). As he explains:

Critical educators must take a stand, working for political or direct democracy, for the direct control of the political system by citizens, for economic democracy, for the ownership and direct control of economic resources by the citizen body, for democracy in the social realm by means of self-management of educational institutions and workplaces, and for the ecological justice that will enable us to reintegrate society into nature (432).

Anarchism or inclusive democracy remain the goal, then, and while McLaren sees anarchistic methods of organization as important means of overcoming capitalism, the State is apparently another such means for him, too. McLaren thus melds the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), the International Marxist-Humanist Organization (IMHO), and Chavismo. Indeed, summarizing his program, McLaren tells us to “[t]hink Zapatismo and Bolivarianismo!” (432). To an extent, such a call overlooks the fact that these political philosophies are at odds with one another regarding the State, which does not so easily “wither away.” McLaren’s Christianity itself also contradicts statism, for, as Tolstoy observed, religion “in its true sense puts an end to the State,” as Christians are to be bound by the divine law of love (agape) rather than allegiance to any authority: “It even seems ridiculous to speak of Christians ruling” (The Kingdom of God Is Within You and Peace Essays, trans. Aylmer Maude, London: Oxford University Press, 1960: 281, 289).

Furthermore, where is McLaren’s commentary on the history of the International Workingmen’s Association (IWMA), or the First International, which saw a split between Marxists and anarchists on the very question of the State? We have already seen that McLaren rejects “Bakuninist adventurism,” whatever that is supposed to mean—though it should be said here that Bakunin stood much more consistently for direct democracy and popular self-management than did his centralist rival Marx. World history, indeed, would likely have turned out much differently if the father of historical materialism had not expelled Bakunin from the First International, leading the anarchist sections to abandon the IWMA for the Jura Federation and the Anti-Authoritarian International instead. Rather than “Zapatismo and Bolivarianismo,” I would prefer to think of “Zapatismo and Magonismo,” or simply “Zapatismo and Anarquismo.” ¡Tierra y Libertad!

Conclusion

McLaren has produced an exceptional volume espousing insurrection from numerous different pedagogical vantage points: historical, geographical, dramaturgical, political, economic, and ecological, among others.

His eclectic philosophical mix incorporating radical Christianity, Marxist humanism, democratic socialism, and anarchism allows for the inclusion of a wide-ranging constellation of movements and figures who have adopted standpoints of resistance to the thanotic and zoöcidal capital-State system—though not without tensions among these worldviews, which conflict to some degree with each other.

In one of the interviews published in the volume, McLaren pointedly asks, “But how to envision a new beginning? That is the challenge of our times” (251). Pedagogy of Insurrection represents a critical contribution to addressing this challenge, one that makes present the “incandescent beauty” of the world, the importance of love, and the possibility of beyond (126)—the dominion of destructiveness notwithstanding.

_*_

Javier Sethness Castro is author of the forthcoming Eros and Revolution: The Critical Philosophy of Herbert Marcuse and a member of the Black Rose/Rosa Negra Anarchist Federation.