In 1992, James O’Connor wrote an article in Capitalism Nature Socialism titled “Think Globally, Act Locally? Toward an International Red Green Movement” in which he handled some burning questions of his times:

“Is it possible to organize an international red green movement, a coordinated response to global capital, to initiate new democratic, ecologically rational, and economically and socially equitable ways of life? To link economic, social, and ecological issues theoretically and practically in ways that would further alternative development paths and visions of the future? To overcome capital’s strategy of divide and conquer, which pits labor against environmentalists, urban workers against small farmers, men against women, majorities against oppressed minorities, and, last but not least, the North against the South?”

In short, can all of the interrelated crises of the modern world be confronted and overcome—as they must be—by a movement that is a match for its planetary antagonist? O’Connor warned that in the absence of this scale and spectrum of struggle, local movements for ecological justice were destined to defeat. Just as the labor movements of the 19th and 20th centuries needed an international organization of workers to resist the predations of the international bourgeoisie, so “the greens” needed to go global.

“If green politics is bereft of global strategy,” O’Connor continued, “local struggles and ecological alternatives will continue to ‘succeed’ meanwhile generating more bad unintended side effects and also failing to reach into the centers of global capital.”

Of course, O’Connor was not ignorant of the many movements of his time. Indeed, he writes, “there is an international movement. Millions of people engaged in social and ecological struggles in dozens of countries…”

But he was concerned that this noble movement was not adding up to the sum of its parts. Even if it was acting globally, often it was only thinking locally: “However, most local groups have little knowledge of similar groups in other parts of the world… hence cannot even speculate about, much less seize, opportunities for strategic and tactical alliances.”

While scattered academics and activists may often connect the dots between diverse movements, the world-historic task remained for these movements, in the terms of Marx’s inaugural address to the International Working Men’s Association, “to master themselves the mysteries of international politics.”

In the quarter century since O’Connor’s article, and near the end of the second decade of the 21st century, we’ve come a long way. The global movements against war, GMOs, the WTO, IMF, and World Bank, and the global movements for climate justice, women’s liberation, and indigenous sovereignty, the World Social Forum process, and more are all carrying us in successive approximations towards organizational forms capable of expressing the power of a global revolutionary movement. There is much to celebrate.

However, the accelerating warming of the poles, the acidification of the oceans, the ongoing mass extinction, and the rise of fascism and war, all remind and reveal that O’Connor’s burning questions have remained mostly without answers. O’Connor had focused his hopes for humanity and nature on a particular organizational goal:

“To develop and strengthen linkages between local groups, activists, and red green intellectuals and scholars around the world calls for an international movement, a ‘fifth international.’ This new international would possess a deep understanding of both ecology and capitalist economy; its ‘line’ would ‘celebrate differences’ as well as commonalities; its purpose would be to develop an international focus and to coordinate a global political strategy.”

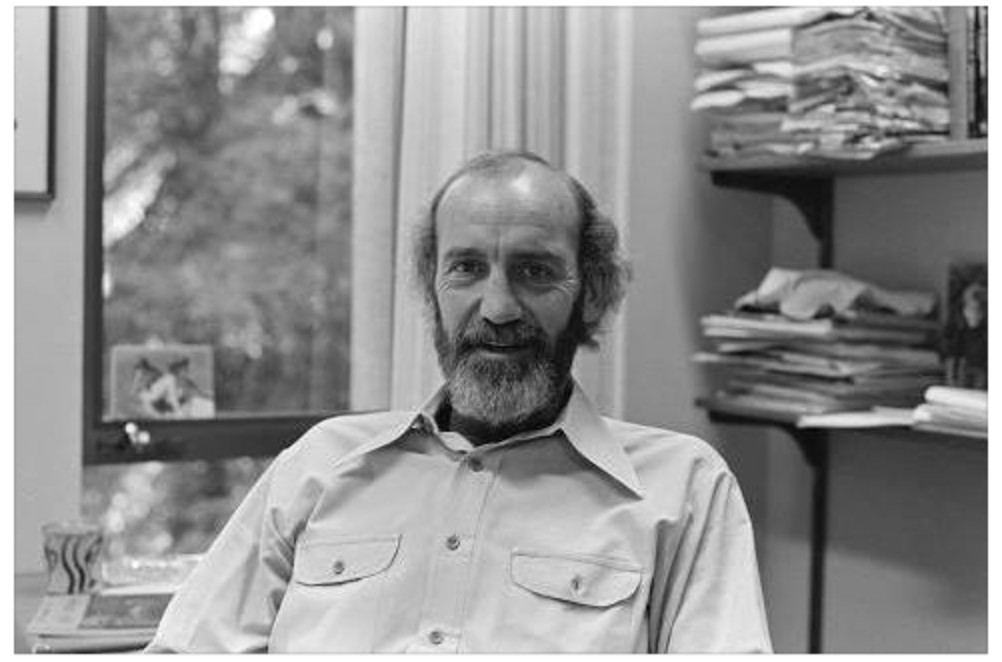

In 2003, James O’Connor passed the journal he founded over to Joel Kovel. Kovel describes Capitalism Nature Socialism in his recent memoir as a “scrawny and impecunious quarterly journal that was also a kind of social movement spanning six continents with the modest goal of transforming history in order to rescue nature from capital” (p. 273).

Kovel shared O’Connor’s search for the organization of an international red-green movement. In 2001 he had written a document with Michael Lowy titled “An Ecosocialist Manifesto,” which began by reformulating the same burning question: “Innumerable points of resistance arise spontaneously across the chaotic ecumene of global capital. Many are immanently ecosocialist in content. How can these be gathered? Can we envision an ‘ecosocialist international?’ Can the spectre be brought into being?”

This short essay is written to confirm and to celebrate that the dream has awoken. In October and November of 2017, over one hundred delegates representing red and green movements from nineteen countries and five continents gathered in a maroon municipality in the countryside of Venezuela and declared: “We have made the decision and the collective commitment to constitute the First Ecosocialist International.”

These words are from a remarkable and revelatory document—a “Combined Strategy and Plan of Action”, whose subtitle reads “Weaving Ourselves to Mother Earth.” It was written over three days in “spirals of dialogue,” and then compiled—a “Plan for the Planet” which was reviewed and approved by consensus in an assembly composed of “an unprecedented alliance of revolutionary subjects.” It is a covenant with Mother Earth, anchored in an ancestral past, and with a route of struggle stretching 500 years into the future.

These words are from a remarkable and revelatory document—a “Combined Strategy and Plan of Action”, whose subtitle reads “Weaving Ourselves to Mother Earth.” It was written over three days in “spirals of dialogue,” and then compiled—a “Plan for the Planet” which was reviewed and approved by consensus in an assembly composed of “an unprecedented alliance of revolutionary subjects.” It is a covenant with Mother Earth, anchored in an ancestral past, and with a route of struggle stretching 500 years into the future.

And there, among the list of founding organizations, alongside the Mesopotamian Ecology Movement, the Kenya Debt Relief Network, the Water Defender’s School from Standing Rock, and many others; alongside guardians of seeds, maroons, and a dozen indigenous peoples, is Jim’s legacy: “Capitalism Nature Socialism.” It was carried there by Salvatore Engel-DiMauro, aka Saed, (who inherited the editorship from Kovel), who participated as a translator and a delegate.

A more prestigious recognition for a radical journal than its place on the masthead of the founding document of a new International is difficult to imagine. Of course, there is no award which bourgeois society and its pet academic institutions can offer for such a distinction. Capitalism Nature Socialism will remain “scrawny and impecunious.” But the more famous and journals “have their consolation,” in the terms of Luke 6:24. CNS has, in the terms of Frantz Fanon, discovered its historic mission, out of relative obscurity, and fulfilled it.

Or rather, initiated it. Those of us who inherit this legacy now have the duty and right of applying ourselves to the analysis, articulation, and amplification of this Plan of Action. There is a fertile vista we may contemplate in applying decades of O’Connor’s analyses and the collective mind of CNS to this document and to the planetary movement it both represents and prefigures. We invite CNS—its authors and readers who make up the “social movement spanning six continents,” and the upcoming conference this summer in O’Connor’s memory to contemplate, to celebrate, and to conclude as he did in the same article: “What is there to lose? What is there to save? The questions answer themselves.”