To Eloísa Vega Castro, en memoriam

How easy it would have been for the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) to join one of the right-wing candidacies currently fighting for the presidency of the republic: PRI, Morena, PAN. How easy to hop aboard any one of those trains to see what can be negotiated and from where profits can be had; to climb atop a caboose to receive the blessing of the top politicians and the promise that the “indigenous question” will be seen to once the presidential chair is taken. How easy. And how irresponsible. And unworthy.

Worse yet: indigenous peoples could only do so by betraying their principles and betraying themselves—canceling their own future. This is why it was impossible for them to succumb, first to flattery, money, promises, and then to scolding, demands, and condemnations.

The CNI (of which the Zapatistas are a part, along with dozens of other tribes, indigenous peoples, and nations of the country) is one of the organizations that holds the upmost credibility and moral authority of the entire nation. It is not free from contradictions and internal disputes. In fact, its discussions are intense, alive. And they are honest—between brothers and between equals. It would be endless to try to list all of those who for whom, with their daily, tireless, unbreakable work, they have managed to build a space of encounter, dialogue, and action among indigenous peoples. Maybe it’s unfair to mention just one person. Or maybe not, for the recognition as “elder brother” or “tata” who—in life and then after death—the people themselves gave to the Purépecha Juan Chávez Alonso.

Over the last five years, the CNI has come to explore peaceful ways of resistance and transformation. The decision to participate in the current electoral process with an Indigenous Governing Council (CIG), in which a spokesperson would appear as a candidate for the presidency of the republic, has been a proposal, above all, to generate the organizational work in the face of what’s to come: the final selling off of the country, and the tearing apart of all vestige of community, collective, or national property.

The programs of the “leading” candidates are really only one program: barely-there cosmetic modifications that make it increasingly difficult to distinguish that which is supposed to differentiate them all. Previously, it could be said that in the struggle of those above, different characters and groups could be found. Today, they have reorganized, and the enemies are now friends and even partners for the cause.

The country is on the edge of the abyss, and the indigenous peoples see it clearly. They have taken up the responsibility to organize against the worst storm currently looming over the country, even threatening the country’s existence. In the CNI you have already seen it, just as millions who do not feel represented in the system of existing parties have seen it.

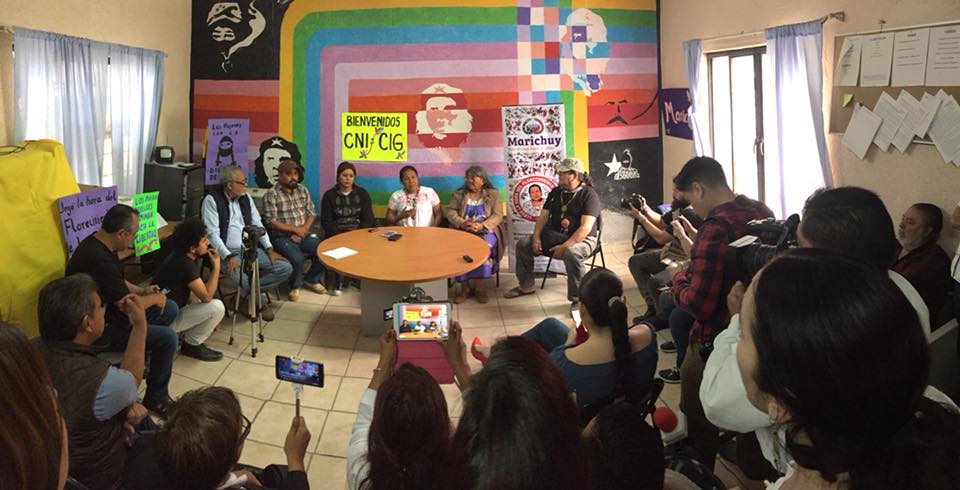

The campaign of María de Jesús Patricio Martínez, Marichuy, has been the only one to surge from the heart of this country that is still called Mexico. Without the coverage of the large media consortia and without the budget of the National Electoral Institute, the indigenous Nahua woman has traveled almost the entire republic to meet with indigenous peoples, agrarian collectives, ejidos, fishing villages, factory workers, students, family members affected by forced disappearances… The trips have always been modest, paid for by the indigenous peoples represented in the CNI, and by the communities that have received them in the four cardinal points of the nation.

She has not promised anyone anything. Not 7 percent economic growth, not scholarships for students, not money for all as a “universal income.” Actually, Marichuy mostly listens. And she summons the affected to look for and create solutions among themselves. It is the most honest campaign (pre-campaign, if we stick to the illogical but legal provisions of the Mexican electoral system) for the presidency of the republic that has come along in a very long time.

Concejalas [councilwomen] and concejales [councilmen] accompany her on these tours. Of course, they also participate in the meetings and dialogues. Everything within the means of those who invite them, often times in enclosed communities up in mountains which the “leading” candidates would never go to.

From the beginning, the CNI and the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), said that it was a very risky proposal. That such task would endanger them. Even so, they insisted on carrying it out.

They met the tedious requirements to register the pre-candidacy and confronted a deeply discriminatory and class-based electoral system, where it is almost impossible to receive legal support for the name of an indigenous candidate to appear on the ballot. The official sabotage being clear, the CNI decided to continue because the pre-campaign was bearing fruit for what was really important: the generation of organizing work and conclusion of agreements.

Before the very unfortunate accident of February 14, the tour of the real country had already involved other incidents, including the assault in Michoacán on reporters who had fallen behind on the caravan on January 21.

Today, another pain accumulates among the members of the CNI. The rollover vehicle accident in which representatives of the CIG were moving in a desert area of Baja California Sur has taken an irreparable toll through the death of Eloísa Vega Castro of the Baja California Sur Network of Support for the CIG, and the serious condition it left the concejal of the Cochimi people, Francisco Grado, in. Marichuy suffered an arm fracture and cranial inflammation. Lucero Yslava Meza, concejala Kumiai; Juana Villa Poblano, CNI committee delegate; and Lorena Moreno Gómez and Ramona Avilés Aviña suffered bruising. In addition, Carlos González and Oscar Espino, of the coordination team of the Indigenous Governing Council, suffered minor injuries.

The CNI has suspended Marichuy’s tour out of respect and solidarity with the deceased compañera and the injured. But it communicates that organizing activities continue. The storm rages. The indigenous peoples face it head on.

_*_

Translated by Linda Quiquivix from the original Spanish: “Marichuy y el CNI en medio de la tormenta”, published by Contralínea on February 16, 2018.