The sense of urgency among activists and citizens of the Global North and their call to take immediate action to save the Amazon forest is wonderful and incredibly hopeful. Yet, much of the discussion in mainstream media as well as among activists is seen through the specific lenses of Western environmentalism. This overlooks critically important aspects of the situation and impedes our collective ability to make truly effective interventions to defend and protect the forest we love.

I began writing this essay as a series of successive posts on social media out of crankiness and after seeing the need to clarify several common misconceptions about the Amazon that circulated virally in popular activist discourses. I point out these misconceptions not to discount the gravity of the situation but to extract the kernel of truth upon which pro-business apologists in the media have already begun to capitalize on debunking—in their case, to dismiss popular outrage and activist responses. It’s important not to die on the hill of these popular arguments because navigating the truth to get at the real story is far more important—in our case, to disarm Bolsonaro and his apologists’ claims of “globalist” hysteria and to ground ourselves politically in ways that can be much more useful to the struggle.

Perhaps the most controversial argument this essay advances is one that is important to make: it is the need to disabuse ourselves of the misconception that the ongoing fires are primarily driven by US demand for meat consumption. While factory farming and industrial livestock production is an unequivocally horrific practice that inflicts much harm on animals and the environment, and while it is true that meat consumption is rising globally as a status marker of the growing middle-class in emerging economies, very little, if any, beef or soy feed from Brazil is consumed in the US. The US remains, along with Brazil, a top producer and exporter of beef and soy; the lion’s share of Brazil’s exports in these areas going to China, the Middle East, and most recently, the EU.

Soy in particular is what is called a “flex crop,” an agroindustrial raw material produced under uniform standards that can be sold to many different markets for many different uses, from animal feed to fake meat to biodiesel, plastics, and car seats, among myriad other things. What this means is that Brazilian producers and their transnational corporate allies can hedge against disruptions in any one market by simply selling to another. Case in point: textured vegetable protein (TVP), a staple soy-protein source for many vegan diets, is the exclusive property of Archer Daniels Midland, a transnational corporation heavily invested in Brazilian soy production and processing. While reducing meat consumption is a respectable personal choice for many other reasons, boycotting hamburgers in the name of the Amazon will do very little to affect these companies’ bottom line. On this particular issue, it’s simply not enough to vote with your fork.

Another misconception is that the Amazon is the “lungs of the Earth;” it is not. The Amazon’s net contribution to the oxygen we breathe is close to zero as the forest consumes as much oxygen as it produces. This is not to say that it’s not critical to oxygen cycling, but the Amazon’s true importance to planetary systems is as a primary regulator and distributor of temperature and heat over the Earth’s surface. Thus, if we must use metaphors, we could say it’s more like the “hypothalamus of the Earth.” While not as catchy as the metaphors preferred by celebrities, it frames better the key threat posed by Amazon deforestation in terms of runaway climate change. Increased forest fragmentation, eventually resulting in a drying-out of the system and forest “dieback,” triggering a feedback loop that accelerates global warming, appears ever more likely now than it has been in the past, especially given several years of increasingly severe climate change-related drought in the region.

Another claim, mobilized especially by mansplainers on social media and in the business press to make excuses for their inaction, is that the current wave of fires is not a new phenomenon, and is actually “far below normal” for the season. That is, that although there has been a record number of fires in 2019, this does not mean that the extent of the burning is unprecedented. On their face, the numbers confirm this. But this hides a much darker truth about the present.

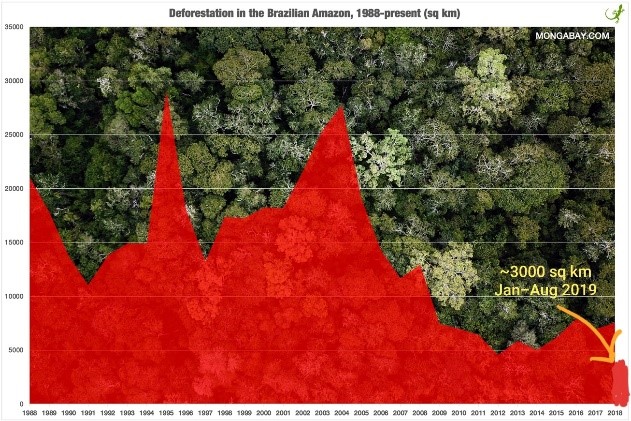

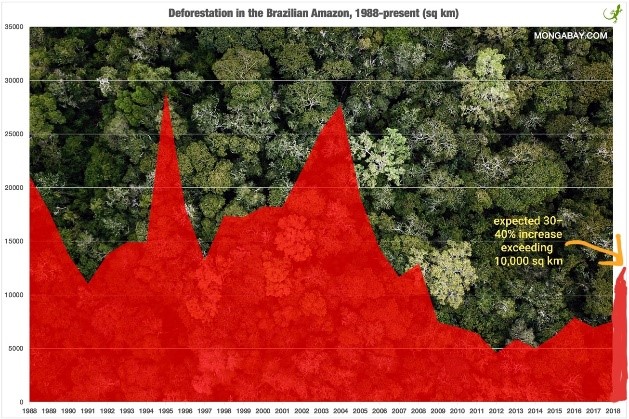

The graphs below are a snapshot of Amazon deforestation, as a measure of total land area deforested, from 1988 to the present, along with some crude hand-drawn annotations extending it to 2019 using what little exists of current data on total area burned and projections for the year. The thing to take away from the data is that, even though the spike in forest burning is absolutely cause for alarm especially under the political circumstances, it is not unprecedented or new. To understand the true implications of the burning, however, we need to take into consideration the location of the fires, not only their number or spatial extent.

I lived in Santarém in 2015–2016, a mid-sized boomtown and key shipping hub at the confluence of the Amazon and Tapajós rivers. I was there doing dissertation fieldwork on peri-urban agroforestry and common practices of backyard gardening that turned the favela districts at the dusty margins of the city into a lush and biodiverse patchwork of food forests, market gardens, and streamside oases. At that time, the soy frontier was advancing north towards the city through the state of Pará, and in the dry season there were many days when the smoke was so thick, I could barely go outside for extended periods of time. Fires and forest clearing are a seasonal constant in the region as agribusiness continues on its march. And at the household level, traditional practices of controlled burning to amend the soil and produce charcoal are a daily feature of Amazonian life. So, while the uptick in fires is a departure from the last decade or so, when government monitoring and enforcement had been at its strongest and deforestation had declined by 75%, the numbers show that compared to the bad old days, the extent of burning is not yet anywhere near its historic peaks.

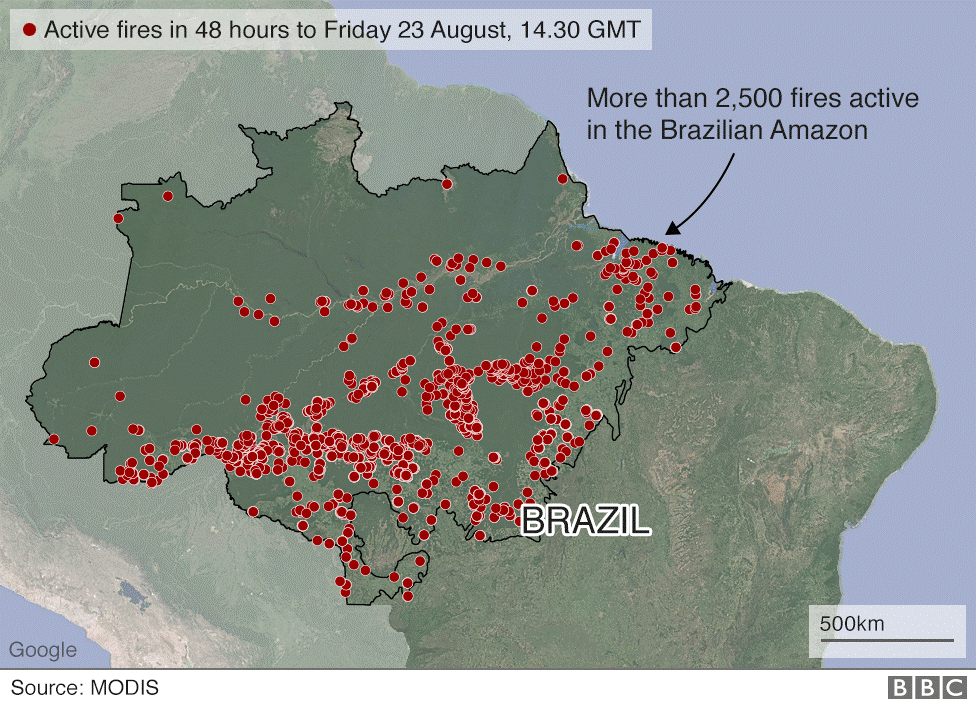

But what I found to be more important than how much is burning is where the fires are happening now—a tale of two maps, as shown below.

The spatial distribution of fires is not random or accidental, nor is it the result of Bolsonaro’s seemingly insane whims. The current fires appear to be occurring both on privately owned land, eating through the required areas set aside for conservation as mandated by the Forest Code, and in and around the designated “conservation units”—the vast mosaic of indigenous territories, protected areas, and extractive reserves where thousands of the Amazon’s traditional communities sustain their livelihoods by managing the forest.

The fires burning now are political. They are not simply driven by the impersonal winds of “the market,” though filthy lucre is always the ultimate goal and the economic pressures of the last five years (deep recession, austerity, and a sluggish recovery) has intensified deforestation, exploitation, and open conflict on the frontier.

The fires are also expressions and instruments of power and struggles over race, class, land, and resources that have been going on for centuries, forming the specific terrain of Brazilian politics. They are about the historical revenge of the ruralistas (the colonial ruling class of the agricultural frontier) against the indigenous tribes and other traditional “forest peoples” – rubber tappers, petty extractivists, quilombolas (descendants of enslaved Africans who escaped into the forest centuries ago), and river communities – who dared to stop the rampant exploitation of some of the planet’s most resource-rich areas in its tracks, claiming their right to maintain the forest as a precious commons for the world’s sake as well as their own.

Bolsonaro, who built his campaign on racist and genocidal rhetoric against indigenous and traditional peoples, was elevated from the extremist fringe to the presidency as the champion of the large landowners, ranchers, loggers, miners, and agribusiness interests represented by the ruralistas who have been salivating over this land for decades. From day one, Bolsonaro has systematically throttled the network of government agencies and NGOs responsible for conservation oversight and, with the final blow to IBAMA, the federal monitoring and enforcement agency now stripped of its powers to stop deforestation on the ground, he made good on his promises by giving his supporters a green light to sack the reserves and smoke out all the forest peoples who stand in their way.

What’s at stake in this wave of fires—underlying all other issues—is the existential struggle for land rights and sovereignty for indigenous and traditional peoples, the socio-political bedrock of forest conservation in Amazônia. Bolsonaro and his coterie, hand in hand with global finance and transnational corporations, are waging genocidal and ideological war against forest peoples and the hard-won, deeply democratic, and transformative model of socio-ecological politics they have built over the last 30 years. What they created, and fight for now in their struggle for cultural and bodily survival, is a paradigm that changed the game of environmental politics in the Amazon and could change the game for our whole planet if we really took the time to understand it.

If there is one text that should be required reading to understand the current moment, it would be Susanna Hecht and Alexander Cockburn’s seminal book, The Fate of the Forest. It remains arguably the best account in the English language of the struggles over deforestation during Brazil’s military dictatorship in the 1970s and 80s, the transition to democracy, and the powerful role of “Brazilian society’s most marginalized members asserting their citizenship through claims of identity, history, and territoriality” in shaping the country’s 1988 Constitution, which codified land rights and sovereignty for traditional peoples and laid the groundwork for creating the most sophisticated system of socio-ecological reserves in the world. Hecht and Cockburn’s book provides some of the essential political history and ideological/scientific frameworks behind the “ecology of justice” that protects and maintains the forest and its inhabitants: the historical, political, cultural, and ecological product of a democratic process of collaboration, popular agitation, and state-making from the bottom up.

Socioambientalismo, as they call it in Brazil (literally translated as “socio-environmentalism”) has at its core an ethic and science of conservation based on a matrix of inhabited, human-managed ecosystems, and working landscapes. It is the living, constantly evolving product of social movements and traditional peoples organized in struggle, and an amazing example of what is possible when marginalized peoples have the social and political space for self-determination and become active, conscious participants in setting the terms that shape the world. I saw this remarkable process of grassroots democracy in action at a meeting of the National Council of Extractivist Populations in 2015, as community members sat in circles with movement leaders, academics, maps, and government agencies to craft land use policies that worked for them, legitimizing their way of life and the ecological services it provided.

Amazonian socio-environmentalism, along with its successful articulation of what Hecht and Cockburn describe as a “new type of social politics that arose… from a lost and invisible populace into a politics of citizenship that has sought to protect political rights, and amazingly, Nature itself,” walks with and inspires a whole array of non-US/Eurocentric ecological politics in the Global South. It compels us to rethink much of what we know as “environmentalism” in the advanced industrial capitalist societies. It challenges the received wisdoms that assume a fundamental opposition between human society and non-human nature, and the Malthusian premise behind the “tragedy of the commons” that assumes humans, as resource maximizers, will always degrade their environments, despite thousands of years of evidence to the contrary. Given the fateful choice humanity faces today—between changing our fundamental relationship with our environment or facing planetary devastation and mass extinction—shaking up some of these long-held ideas might be a very, very good thing.

The Amazon is so much more than the sum of its biophysical processes and feedback loops; the forest also thrives because of, not despite, the people who have lived with it for generations. Everyday Amazonians—the subsistence and small-scale producers who were at the heart of my research in Santarém—are remarkably good at growing trees, reflecting an agroecological common sense informed by layers of indigenous, African, and traditional peasant knowledge.

Traditional uses of managed fire to improve soils also reflect the legacy of anthropogenic terra preta soils found throughout the Amazon, the ecological product of thousands of years of indigenous human labor that cultivated the forest, and a secret ingredient to much of its incredible ethnobotanical wealth, productivity and resilience. One cannot get the whole story behind the reprieve of the last decade and a half of deforestation decline without considering the role of anthropogenic re-forestation, land management, and the relationship between culture and territory that is integral to forest livelihoods and the life of the forest as a whole.

It is life-changing and world-changing to be able to even imagine a new set of social and institutional relationships to nature, to valorize indigenous and traditional knowledge in ways that don’t compartmentalize them into essentialized premodern fantasies for white consumption, and to see working models of socio-ecological systems that enhance ecosystems with human density rather than degrade or destabilize them. It allows us to critically discern and differentiate “human nature” and social nature writ large from capitalist nature. This understanding opens a whole other dimension of possible ways to see ourselves in the world, and points toward new pathways by which we can transition out of the Capitalocene to a true Anthropocene, where we relearn how to take our rightful place on the land, one species among many, but a keystone species of our ecosystems, consciously and collectively working to build and sustain resilient, abundant, and livable landscapes for future generations of human and non-human life.

This transformative vision—and the survival of the peoples and social movements who articulated and enacted it—is what is fundamentally at stake in the struggle against Bolsonaro in the Amazon, and by extension, for the survival of the planet. Focusing narrowly on consumer politics as our ecological responsibility reinforces the colonial erasure of the invaluable knowledge and political agency of the indigenous and traditional peoples who have struggled mightily and sacrificed so much to maintain the living heart of the forests that sustain us all, in the Amazon and elsewhere. We owe them much more than self-serving, feel-good half measures. Their knowledge and agency in protecting the forest is as important as the data given by climate scientists on the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Concerned environmentalists and anti-capitalist activists can help Amazônia most effectively by putting the struggles of indigenous and traditional peoples front and center in our narrative as we educate people about the crisis, and demand to protect their rights to land and sovereignty from the forces that are doing incalculable damage, not just to the trees but to the human beings whose lives and livelihoods are inseparable from the life of the forest. We can do right by them by allowing their voices and demands to take the leadership role that is their due as we build international solidarity across borders and by putting international pressure on any and all relevant institutions of governance, commerce, and civil society to demand that the integrity of demarcated reserves, and the inalienable right of indigenous peoples to their ancestral territories, as enshrined in the 1988 Constitution, must be respected and enforced.

We can change the course of destruction in Amazônia and in the whole world by letting Amazônia change us, by recognizing the special contributions of Amazonian peoples and social movements to a revolution in socio-ecological thinking that holds inestimable value for all of us while we attempt to transcend the global socio-ecological crisis. It requires those of us who live in the advanced capitalist societies to humble ourselves, de-center our own received green-imperialist wisdoms, and try to understand the socio-ecological ideas, perspectives, and struggles of indigenous and colonized peoples. Rather than being their “saviors,” it requires us to walk with and support social movements on their own terms.

Principles of socioambientalismo echo a host of other struggles throughout the world in which social justice is inseparable from ecological protection: movements for food sovereignty, climate justice, water protection, defense of sacred lands, watershed and salmon restoration, agroecology, and more from the forests of the Amazon to the plains of Standing Rock. We cannot save the Amazon or the Earth without fighting for the people who have made its remarkable ecosystems possible.

Na Floresta Tem Gente!

In the Forest, There Are People!

Learn more about and support movements of forest peoples in the Amazon:

Articulation of Indigenous Peoples in Brazil:

http://apib.info/category/ingles

National Council of Extractivist Peoples:

http://www.memorialchicomendes.org/who-are-we/?lang=en

Xingu Network:

https://www.xingumais.org.br/home

Instituto Socioambiental:

https://www.socioambiental.org/en/about-isa